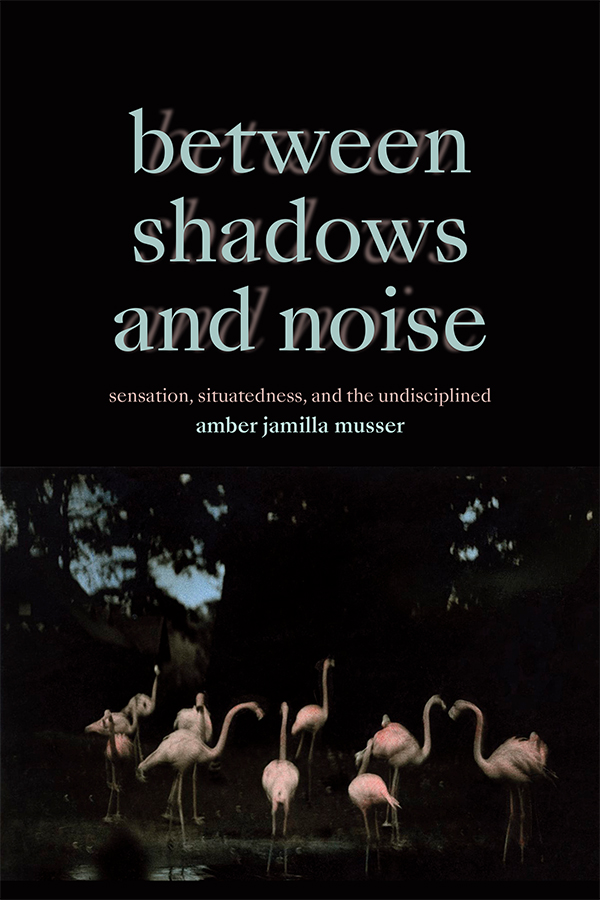

Musser opens her newest monograph with a discussion of Ming Smith’s 1988 photo, “Flamingo Fandango (West Berlin)” in order to draw out the theoretical potency of her title’s key terms, noise and shadow. The pink of the flamingos is their noise, she says; it is a color that draws attention to the birds’ “affective and sensual milieu” (2). The pink noise pops out at viewers and situates the flamingos as unable to be contained. They overflow their coloration, Musser notes, and suggests that they (and all entities?) are “multisensory and attentive to fabric of social relation” (5).

The photo’s blurred background, on the other hand, constitutes the shadows accompanying pink noise. Shadows reflect the space and form of bodies, shadows hold the extension of objects into the spaces around them. As such, shadows lure us to attend to what lies clearly but often ineffably between bodies. Shadows evoke dynamics of “repression, disavowal,” that form some (minority) bodies in negative relation to predominant systems of ontology (avowal) and epistemology (expression) (4). Musser conclues that shadow and noise display how our wayward senses have been trained into a disciplined ‘common sense.’ The terms suggest a task for theorists, which is to linger with what exceeds or cannot be incorporated into this common sense.

To dwell with the wispy fibers that connect noise to its shadows requires what Musser calls “body work.

In concert with Simone de Beauvoir, Jasbir Puar, José Muñoz, Musser develops “body work” as a theoretical tool for sitting with difference, for complexifying vocabulary for gender, race, and racialization, and for foregrounding what Glissant calls the primacy of opacity. She seeks to develop strategies for non-white, diasporic, and disabled bodies to think and be otherwise. Or as she herself puts it,

“these analyses show the interpretive possibilities offered by sensual forms of knowing, complexifying how we have thought about representation and offering an argument for critical situatedness” (15)

To accomplish this sitting-with-difference, Musser’s chapters examine Jordan Peele’s film, Us (2019, Katherine Dunham’s dance, Shango (1945), Samita Sinha’s performance artwork, This Ember State (2018), Teresita Fernandez’s photograph, Puerto Rico (Burned) 6 (2018), and Titus Kaphar’s sculpture, A Pillow for Fragile Fictions (2016), and then ends poignantly with Musser’s own version of (Lorde’s) Cancer Journals, which discuss Musser’s diagnosis and treatment for acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Though Musser’s chapters are rich and interesting, I confess that I find the theoretical prompting of her introduction more exciting. I didn’t find the notions of noise and shadow essential for tracking the arguments of her chapters and, to me, the assortment of theoretical objects in these chapters (film, dance, performance art, photography, sculpture, and one’s own body as a medical object) felt a bit arbitrary, even though I know full well that Musser has the theoretical muscle to theorize what I might call the shadows between the noise of each chapter, a kind of fascia that would have made her arguments both stronger and more flexible.

Nevertheless, I have been moved and changed by Musser’s discussion of shadow and noise. For myself—and drawing on some but not all of Musser’s words—I would rather stress the affective and cognitive (affecognitive) difficulties of “sitting with difference” and the theoretical potency of shifting to affective registers of noise (impact, being-affected) and shadow (elusiveness, slyness, ineffability) as cagey end-runs around the rational captures of representation.

Noise, after all, traverses the distance between an object and receiver—it is displaced from the object and slams into the sensorium of the receiver. Shadow, too, is a visual displacement, a sign that the shadow’s source is taking up space and blocking light. Shadows show the form of something that is not there. This form is not the shadow, but stands slightly adjacent to the shadow and produces it. Musser’s discussions of shadow and noise suggest their catachrestic uses as well. Proust’s madeleine dipped in lime blossom tea yanks all of Combray out of the teacup, showing how taste can produce shadow. Likewise, the smell of one’s mother or one’s childhood bedroom can produce the subtle shadows of one’s youthful self; more frustratingly, a smell might produce a déjà vu that hovers on the edges of memory, stinging it like a wasp but never resolving into the solid form of memory.

I am, in short, drawn to the centrality of a non-representational displacement in Musser’s concepts of noise and shadow. Let me offer two too brief examples.

First, in Mira Nair’s The Namesake and Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men, both released in 2006, these very different directors cut away from narrative to show characters’ feet. Nair spreads the motif across three characters, the wife, the husband, and the son, by showing feet slipping into and out of shoes. Are shoes the shadows of feet, a form displaced from the object? Is Nair’s occasional but determined cutaway to feet her fluid means of expressing the multiple displacements of diasporic and gender identities while avoiding leaden dialogue? Whole worlds open up to the side of these shoes, both interior and existential worlds, and exterior and political worlds; and when the husband dies, Nair films the wife flitting agitatedly through the house before cutting to a frontal closeup of her now naked feet, no shoes, at the threshold of her open garage. Are these naked feet a reaffirmation of the cis-het family values so prominently displayed in the film—or a whispered possibility that the wife might now live (quite well) without a man? In Children of Men, Cuarón only cuts to the feet of the protagonist, Theo (Clive Owen), starting with a very odd (and therefore very noisy) telephoto shot of his feet in the foreground, with Theo’s body stretched out obliquely into the depth of the screen behind the feet. The camera tracks Theo’s naked and shoed feet rather obsessively through the film, but the shots remain noisy in that they clearly mean more than they show, even though it remains unclear exactly what they mean aside from the general sense that the feet are displaced from Theo’s possession into challenging material and sensual relations with their environment.

Another more personal example arises from the fact that everyone on my semi-circle here in North Carolina has arcane language written into our house deeds, language that specifically forbids trailers, farm animals, “Jews, and other minorities.” It’s horrible and not legal (not even here in the South). The words hover around us white and non-Jewish property owners, a shadow that reminds us of various awful histories spewing out from those classed and racialized words in ways that are not representational but affective. The language forces us to dwell inescapably with differences of time and being that we cannot eradicate. Or not easily. We have each been told by lawyers that the only way to delete the language in the deeds is for someone to challenge our home ownership in court, on the grounds of this language. Only then could the court system strike out the language and change the deeds. I find this fact bizarre and more than a little disturbing. The shadow of history has to become the noise of litigation in order for it to be rendered a different kind of shadow (of history erased). Perhaps it’s better to have the disgusting language remain, a gut-wrenching reminder of the sensual entitlements of whiteness and the wide range of sensorial precarities this geographical terrain once wielded so complacently.

Read Musser’s book, it is a gem. It is a noisy book, we might say, that produces long shadows that creep into the noise and shadows of our own lives.

I’ve been thinking again about the limits of our aspirations to a social science with the examples of ethnographic accounts, there is a certain allure to the promise of “thick” accounts but there aren’t really principles for our choices of what to focus on (what to count, account for) and what is just background “noise”, how much time before and after an “event” is needed to be covered, how much context of place and or social infrastructures (political-economies and all) is to be considered, and that doesn’t even get into all of the un-conscious processes at work in generating the sorts of object-relations that we can consciously recount. Not to even get into what happens when notes, or snapshots or taped recordings have to be translated after the fact into something like a monograph or paper or such, and how much that is about the demands of the moment at hand vs whatever brought us to the scene in the first place (and or how being-in-the-midst-of-things calls for negotiations that shift that initial trajectory) Our dreams of capturing something, re-presenting something, maybe need to make way for the realities of bricolage and the possible affordances of such collages as possible spurs for what follows?

LikeLike

doing some reading of the poet Kenneth white who was in deleuze & guattari’s seminar (probably the one who brought them references on nomads) he notes:

For the question is always

how

out of all the chances and changes

to select

the features of real significance

so as to make

of the welter

a world that will last

and how to order

the signs and the symbols

so they will continue

to form new patterns

developing into

new harmonic wholes

so to keep life alive

in complexity

and complicity

with all of being –

LikeLike

feelings in common?

https://convergingdialogues.substack.com/p/345-how-culture-creates-emotions

LikeLike